When Institutional Investor published its first issue in April 1967, Gerald Tsai Jr. was without a doubt the most influential investment manager in the world.

A 1968 Newsweek story, “Tsai and the Go-Go Funds,” proclaimed: “No man wields greater influence in the world of funds than Gerald Tsai Jr.” Gil Kaplan, II’s founder, had lavished similar praise on Tsai at II’s first investor conference (which attracted 1,521 money managers), in January 1968, describing him as “a man who bears the same relationship to performance funds that Joe Namath does to the American Football League, the man who broke the price ceiling on talent.”

The cause of this notoriety? Tsai pioneered “performance funds” — what we would today call aggressive growth funds — that used momentum instead of the de rigueur dividend discount model as the source of his investment decisions. His “go-go” approach revealed an entirely new way to invest, and, according to Edward C. Johnson II, the founder of Fidelity, it was “a beautiful thing to watch his reactions. What grace, what timing — glorious!”

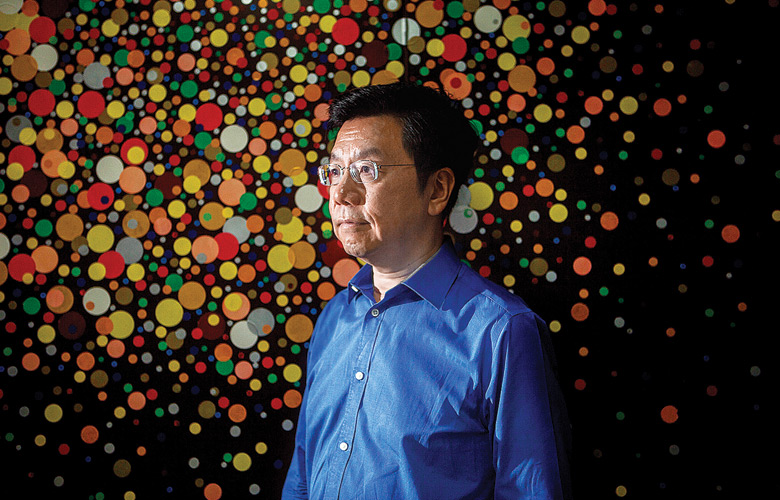

As this is my final column for the final print edition of the magazine (but fear not! I’ll be writing just as much online), I decided to put down a marker and predict who in the next five years will similarly disrupt asset management. It’s not going to be Elon Musk or Jeff Bezos or even Richard Craib. It will be Kai-Fu Lee.

If you’re asking yourself, “Who is Kai-Fu Lee?,” then you’re ready to be disrupted.

In brief, Lee is the founder and CEO of Sinovation Ventures and president of Sinovation Ventures’ Artificial Intelligence Institute. But he is much bigger than that.

Lee is an unusual combination of academic innovator, capital markets investor, technological entrepreneur, and celebrity — kind of an amalgam of Jack Treynor, Cliff Asness, Steve Jobs, and Katy Perry.

Lee’s entire career — which placed Lee at the nexus of technological breakthroughs and commercial deployments — has prepared him for the role of disruptor. He is one of the creators of artificial intelligence, having developed the world’s first speaker-independent, continuous speech recognition system as his Ph.D. thesis at Carnegie Mellon in 1988. He was an executive at Apple and Silicon Graphics, then founded Microsoft’s Beijing research lab — which in 2004 MIT Technology Review called “the world’s hottest computer lab” — in 1998 and Google China in 2005. Now, as the founder of Beijing-based Sinovation, Lee is investing in early-stage AI companies.

His successful tech career and ongoing mentorship of young Chinese entrepreneurs and scholars have earned Lee star status, attracting more than 50 million followers on the Chinese microblogging platform Sina Weibo. (Ray Dalio, by contrast, has about 129,000 Twitter followers.)

Critically, Lee’s terroir is China — and China, as Lee often points out, has the three necessary ingredients for the development and commercialization of AI: scientific talent, data, and government support.

First, talent. China has a large and growing army of gifted engineering and math graduate students. These students, along with world-class talent at China’s tech giants (e.g., Alibaba, Baidu, Tencent), start-ups, and universities, have been prolific in their R&D, filing more than 8,000 AI patents in the five years to 2015 — a 190 percent growth rate that outpaces other leading markets significantly — and publishing more deep learning–related papers in journals than researchers from any other country.

Second, data. Data is the critical ingredient in building transformative AI technology, and, according to The Economist, China is “the Saudi Arabia of data.” Science magazine reports that China now has more than 750 million people online, and more than 95 percent of them access the internet using mobile devices: “In 2016, Chinese mobile-payment transactions totaled $5.5 trillion, about 50 times more than in the United States that

year. . . . Even toilet paper in public restrooms is now being dispensed, in limited amounts, after a facial scan.”

Equally important, The Economist points out that “Chinese do not seem to be terribly concerned about privacy, which makes collecting data easier.”

Third, government support. In 2017 the Chinese central government put forth a Next Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan, which calls for China to be the world leader in AI by 2030. The plan includes hundreds of billions of dollars of funding from the central and regional governments. Cynics might scoff at this as another futile command-and-control five-year plan, but many experts agree with Andrew Ng, the former chief scientist at China’s largest online search firm, Baidu, that “when the Chinese government announces a plan like this, it has significant implications for the country and the economy. It’s a very strong signal to everyone that things will happen.”

Lee alone has the scientific knowledge, investment expertise, mercantile bent, personal and professional credibility, and outsider’s mentality to catalyze the current technological and social AI phenomena in China into a disruptive investment juggernaut.

Although he has not explicitly stated such an intention, he has offered telling clues. In his 2017 commencement address at Columbia University, he told graduates, “In the next ten years, all financial companies will be turned upside down, with AI replacing traders, bankers, accountants, and research analysts.” He added, “In 2016 my personal investment algorithm returned eight times more than my private banker.” The absolute clincher is his view that “our brains are never intended to make smart investment decisions. Machines are the ones who should do this for us.”

More generally, he has regularly said it is an engineer’s responsibility to make the world a better place. What more fitting application of AI than to help beneficiaries achieve a more secure financial future?